Does systems thinking lead to systems that can learn as they evolve (or devolve)? How does a service system continue to learn about purposes (and objectives and goals) in its wholes and its parts? When a service system learns that change is called for, can that system consciously act to evolve (or devolve)?

Focusing on definitions of science and of systems thinking can lead to thinking about a static thing, rather than intellectual virtues that changes over time. Applying systems thinking to science, the intellectual virtues of episteme (know why), techne (know how) and phronesis (know when, know where, know whom) can each or all evolve. Actually, they coevolve, because the why, how, when, where and whom are all changing simultaneously.

Many of today’s services systems are under stress, possibly reaching a point of unsustainability. Does (or would) systems thinking help? To be concise, let’s try some responses to the three questions at the outset of this essay.

- Does systems thinking lead to systems that can learn as they evolve (or devolve)?

- A system in which systems thinking has contributed towards its design should have had features or properties included that are appropriate for its environment. If the environment changes, the fitness of the system may or may not degrade. A system intended for volatile environments may be have been designed to respond to change, or to fail — potentially gracefully — with signals that a more appropriate replacement should be put in place. The range of designs from fragile to “over-engineered” reflects different approaches to handling environmental change.

- How does a service system continue to learn about purposes (and objectives and goals) in its wholes and its parts?

- A service system — potentially socially constructed, and/or developed from natural resources — can be designed for its whole to serve both a collective (e.g. a community, a nation) and/or an individual. In addition, parts of that system may satisfy goals for others, as a byproduct. The wants and needs of service recipients may evolve, however.

- When a service system learns that change is called for, can that system consciously act to evolve (or devolve)?

- As the function provided by a system degrades or fails, the choices are either to (i) decommission the old service and start up a new service, or (ii) change the existing systems as it continues to operate. This latter choice requires a system that not only adapts to its environment, but also learns.

A service designed with systems thinking may have a productive lifespan that is short or long. Designing a service system that remains viable over a brief life cycle can be a challenge. Designing a service system that can learn and appropriately evolve with a highly variable environment is a bigger challenge.

In systems thinking, the idea of learning has been well developed. The remainder of this essay outlines some of the foundational appreciation on learning from systems research, and adds some recent theories coinciding with the practice turn in contemporary theory [Schatzki, Knorr-Cetina, von Savigny (2001)].

- A. A system can maintain its purpose under constant conditions by adapting, and under changing conditions by learning.

- B. Learning can typed at multiple levels: (1) change within a set of alternatives; (2) change in the set of alternatives; (3) change in the system of sets of alternatives; and (4) change in the development of systems of sets of alternatives.

- C. Both physical systems and human systems can learn, if sufficient resources are reserved for long term maintenance.

- D. In human systems, social participation is a process of learning and knowing that includes meaning, practice, community and identity

Systems thinking about systems thinking should include a greater emphais on design for learning. Each of the above assertions is supported in the sections that follow.

A. A system can maintain its purpose under constant conditions by adapting, and under changing conditions by learning.

Designing beyond the minimal level of viability requires a perspective on explicit and/or implicit purpose(s) for a system. While there are other techniques that speak to purpose, Ackoff (1981) advocates a process of idealized design. The response(s) of the system to changes in the environment can then be labelled.

The product of an idealized design should be an ideal-seeking system. Such a system must be capable of pursuing its ideals with increasing effectiveness under both constant and it changing conditions; it must be capable of learning and adapting. [p. 126]

Ackoff first defines his meaning on adaptation, in the context of a company, and then more generally in a broader range of systems. A contrast between adaptation and evolution is provided.

To adapt is to respond to an internal or external change in such a way as to maintain or improve performance. The change to which adaptation is a response may be present either a threat or an opportunity. For example, the appearance of a new competitor may present a threat; the disappearance of an old one, an opportunity. Both require an ability to detect changes that can or do affect performance and to respond to them with corrective or exploitative action. Such action may consist of the change in either the system itself or its environment. For example, if it suddenly turns cold, one can either put on additional clothing (change oneself) or turn up the heat (change environment). Furthermore, the change to which adaptation is a response may occur either by choice or without it. The demise of a competitor, for example, may occur independently or because of what the corporation’s does.

The concept of adaptation used here is much richer than of the one used in association with the theory of evolution. In that theory, adaptation refers to only involuntary responses to external changes, and the responses consist of internal changes. This restricted connotation of the concept derives from the fact that the theory of evolution is preoccupied with nonpurposeful systems, and when it deals with purposeful systems it is not concerned with their purposefulness. Here we are preoccupied entirely with purposeful systems and their purposefulness. [pp. 126-127]

Next, learning is defined with two subtypes: controlled and uncontrolled.

To learn is to improve performance under unchanging conditions. We learn from our own experience and that of others. Such experience can be controlled, as in experimentation, or uncontrolled, as in trial and error. For example, if we improve our rifle shooting at a target with repeated tries, we learn. If, after we have done so, a wind comes up that makes us miss the target, adaptation is called for. We can adapt either by adjusting the sight on the rifle or by aiming into the wind. [p. 127]

At another level is double-loop learning, where the (primary) purpose(s) of a system can be differentiated from a purpose oriented towards learning.

Because learning and adaptation, as I deal with them, are purposeful activities (i.e., matters of choice) they can themselves be learned. Learning how to learn and adapt is sometimes called double-loop learning. If we did not have such a capability, this chapter would have been written in vain because it is intended to facilitate just such learning.

A system cannot learn and adapt unless its management can. Therefore, an ideal-seeking system must have a management system that can learn how to learn and adapt. [p. 127]

Again, the emphasis in Ackoff (1981) is on companies, so there’s a major interest in learning by management. There’s a slightly more general discussion on learning in Ackoff and Emery (1972) On Purposeful Systems, but there’s no escaping purpose (viz. teleology — the philosophy of ends) that tends towards human-centricity.

B. Learning can typed at multiple levels: (1) change within a set of alternatives; (2) change in the set of alternatives; (3) change in the system of sets of alternatives; and (4) change in the development of systems of sets of alternatives.

Predating the work of Ackoff (1981) is Gregory Bateson’s categorizations from 1972. Bateson writes more generally, so that learning doesn’t necessarily have to be associated with human systems. Learning can be observed as a matter of course in nature.

The “Learning” of Computers, Rats, and Men

The word “learning” undoubtedly denotes change of some kind. To say what kind of change is a delicate matter. [….]

Change denotes process. But processes are themselves subject to “change”. The process may accelerate, it may slow down, or it may undergo other types of change such that we shall say that it is now a “different” process. [….]

[Zero learning] … is the case in which an entity shows minimal change in its response to a repeated item of sensory input. […] [p. 283]

Within the frame of our definition many very simple mechanical devices show at least the phenomenon of zero learning. The question is not, “Can machines learn?” but what level or order of learning does a given machine achieve? [….] [p. 284]

Zero learning will then be the label for the immediate base of all those acts (simple and complex) which are not subject to correction by trial and error. Learning I will be an appropriate lavel for the revision of choice within an unchanged set of alternatives; Learning II will be the label of the revision of the set from which the choice is to be made; and so on. [p. 287]

After some expositions on the categorizations of learning, Bateson provides a helpful summary of definitions.

Zero learning is characterized by specificity of response, which — right or wrong — is not subject to correction.

Learning I is change in specificity of response by correction of errors of choice within a set of alternatives

Learning II is change in the process of Learning I, e.g., a corrective change in the set of alternatives from which choice is made, or it is a change in how the sequence of experience is punctuated.

Learning III is change in the process of Learning II, e.g., a corrective change in the system of sets of alternatives from which choice is made. (We shall see later that to demand this level of performance of some men and some mammals is sometimes pathogenic.)

Learning IV would be change in Learning III, but probably does not occur in any adult living organism on this earth. Evolutionary process has, however, created organisms whose ontogeny brings them to Level III. The combination of phylogenesis with ontogenesis, in fact, achieves Level IV. [p. 293]

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, ontogeny can be defined as “the origin and development of the individual being”. Accordingly, ontogenesis is “the origin and development of the individual living being (as distinguished from phylogenesis, that of the tribe or species”).

Bateson’s view on learning does not necessarily involve purpose. The perspective is more general than just in human systems, and thus includes evolutionary process.

C. Both physical systems and human systems can learn, if sufficient resources are reserved for long term maintenance.

Learning, as a systems concept, can be extended from the usual domain of living systems even towards non-living systems. Brand (1994) had an interest in studying organizational learning, leading to research into a domain with greater longitudinal history: built physical environments, commonly known as architecture. There’s an ongoing coevolution between a building and its occupants.

Age plus adaptability is what makes a building come to be loved. The building learns from its occupants, and they learn from it. [p. 23]

As an alternative to considering the human at the centre of the universe with a built structure as his or her environment, a building as a system can include the occupant as part of its environment. Buildings can outlive their occupants, and may or may not be constructed to endure natural conditions. Given the longevity of a building, looking into its future is a challenge.

All buildings are predictions. All predictions are wrong. [p. 178]

The iron rule of planning is: whatever a client or an architect says will happen with a building, won’t. Architects always want to control the future. So do clients. A big, physical building seems a perfect way to bind the course of future events. (“Once we move the company into the new building, then we can use it to limit our growth.”) It never works. The future is no more controllable than it is predictable. The only reliable attitude to take toward the future is that it is profoundly, structurally, unavoidably perverse. The rest of the iron rule is: whatever you are ready for, doesn’t happen; whatever you are unready for, does. [p. 181]

Brand provides background on the earlier writing on human learning, with references to Bateson and Argyris. The concepts of system andenvironment are preserved, and three levels of learning are described.

Human learning has been distinguished into three fundamental levels, the first of which in fact services habit. The keepers of a routine like to endlessly refine its detail, tweaking the environment to serve it ever more precisely. Far from threatening the the routine, this kind of incremental refinement enshrines it always further. Organizational learning theorists such as Gregory Bateson and Chris Argyris refer to it as “single-loop learning” — like a thermostat turning the heater on and off to keep the room at a comfort level. The learning is “single-loop” because it responds to a a simple feedback loop: keep the room near 67 degrees Fahrenheit; keep the stting room a restorative refuge for the duchess; keep the bathroom clean and cleanable.

This kind of learning that threatens habit is up a level — “double loop learning.” Instead of minor adjustments, major readjustments are called for. The thermostat is reset to a different temperature entirely. This is the second, higher, loop of feedback, declaring that the entire habit, not matter how perfectly refined, no longer serves the larger purpose. Sorry Duchess, but the sitting room has to become a bedroom for the grandchild who is visiting more often now. Do you suppose you and the dogs could move to that nice corner room with the view towards the hills? Sorry, accounting department, you’ve outgrown the electrical capacity of this part of the building. We’ve got to recable, and how would you feel about a raised floor so that the next change will be easier?

A third level of learning is “learning to learn.” Raised floor is one example. This book is another. While single-loop refines habit, and double-loop changes habits, learning-to-learn changes how we change habits. An organization that fires the janitor and hires a facilities manager is taking a new relationship to change in the building, effectively shifting from a statis manager to a change manager. [p. 167]

Buildings can be designed to learn. Since buildings are durable, the funds allocated in period of construction can be compared to those in ongoing maintenance.

The major difference in a “learning” building is its budget. Following Chris Alexander’s formula, there needs to be more money than usual spent on the basic Structure, less on finishing, and more on perpetual adjustment and maintenance. The less-on-finishing part takes forceful management because the architect will want pizzazz in the finish, where it shows, and many artisans are not happy skimping on finish quality. The architect needs financial incentive to hold the line. I have suggested settling on a preliminary design and construction budget, with the architect getting a flat fee — plus a generous bonus if budget and schedule are met. This encourages realism and rewards parsimony.

If you want a building to learn, you have to pay its tuition. [p. 190]

A building is a non-living system. It’s an artifact of human activity. It can coevolve with its occupants and external environment, or behave non-responsively to a level of dysfunction or obsolescence.

D. In human systems, social participation is a process of learning and knowing that includes meaning, practice, community and identity

The dates on the systems references described above should be noted: Bateson (1972), Ackoff (1981), Brand (1994). Many in the systems community are less familiar with advances on learning in human systems, in particular on learning from a perspective of social learning. Wenger (1998) provides not only a complete system of ideas, but also references to alternative points of view. The rise of the domain of communities of practice represents a leap forward as a work of applied philosophy. Trying to understand a theory of practice leads to a path beyond science, and into philosophy. Few people, however, are likely to have read the original 1998 book, and even fewer are likely to have read the footnotes. As a way of encouraging people to look at this work in greater detail, I’m reproducing introductory sections with footnotes reunited into the flow of the main text.

Wenger outlines the domain of learning, from a social perspective. He first clarifies to outline theories focused on alternative aspects of learning, particularly as neurological, psychological or alternative hybrids.

A conceptual perspective: theory and practice

There are many different types of learning theory. Each emphasizes different aspects of learning, and each is therefore useful for different purposes. To some extent these differences in emphasis reflect a deliberate focus on a slice of the multidimensional problems of learning, and to some extent they reflect more fundamental differences in assumptions about the nature of knowledge, knowing, and knowers, and consequently about what matters in learning. (For those who are interested, the first note lists a number of such theories with a brief description of their focus.1) [pp. 4-5]

1. I am not claiming that a social perspective of the sort proposed here says everything there is to say about learning. It takes for granted the biological, neurophysiological, cultural, linguistic, and historical developments that have made our human experience possible. Nor do I make any sweeping claim that the assumptions that underlie my approach are incompatible with those of other theories. There is no room here to go into very much detail, but for contrast it is useful to mention the themes and pedagogical locus of some other theories in order to sketch the landscape in which this book is situated.

Learning is a natural concern for students of neurological functions.

- Neurophysiological theories focus on the biological mechanisms of learning. They are informative about physiological limits and rhythms and about issues of stimulation and optimization of memory processes (Edelman 1993; Sylwester 1995).

Learning has traditionally been the province of psychological theories.

- Behaviourist theories focus on behavior modification via stimulus-response pairs and selective reinforcentent. Their pedagogical focus is on control and adaptive response. Because they completely ignore issues of meaning, their usefulness lies in cases where addressing issues of social meaning is made impossible or is not relevant, such as automatisms, severe social dysfunctionality, or animal training (Skinner 1974).

- Cognitive theories focus on internal cognitive structures and view learning as transformations in these cognitive structures. Their pedagogical focus is on the processing and transmission of information through communication, explanation, recombination, contrast, inference, and problem solving. They are useful for designing sequences of conceptual material that build upon existing information structures (J. R. Anderson 1983; Wenger l987; Hutchins 1995). [p. 279]

- Constructivist theories locus on the processes by which learners build their own mental structures when interacting with an environment. Their pedagogical focus is task-oriented. They favor hands-on, self-directed activities oriented toward design and discovery. They are useful for structuring learning environments, such as simulated worlds, so as to afford the construction of certain conceptual structures through engagement in self-directed tasks (Piaget 1954; Papert 1980). [p. 279-280]

- Social learning theories take social interactions into account, but still from a primarily psychological perspective. They place the emphasis on interpersonal relations involving imitation and modeling, and thus focus on the study of cognitive processes by which observation can become a source of learning. They are useful for understanding the detailed information-processing mechanisrns by which social interactions affect behavior (Bandura 1977).

Some theories are moving away from an exclusively psychological approach, but with a different focus from mine.

- Activity theories focus on the structure of activities as historically constituted entities. Their pedagogical focus is on bridging the gap between the historical stage of an activity and the developmental stage of a person with respect to that activity — for instance, the gap between the current state of a language and a child’s ability to speak that language. The purpose is to define a “zone of proximal development” in which learners who receive help can perform an activity they would not be able to perform by themselves (Vygotsky 1934; Wertsch 1985; Engestrom 1987).

- Socializational theories focus on the acquisition of membership by newcomers within a functionalist framework where acquiring membership is defined as internalizing the norms of a social group (Parsons 1962). As I will argue. there is a subtle difference between imitation or the internalization of norms by individuals and the construction of identities within communities of practice.

- Organizational theories concern themselves both with the ways individuals learn in organizational contexts and with the ways in which organizations can he said to learn as organizations. Their pedagogical focus is on organizational systems, structures, and politics and on institutional forms of memory (Argyris and Schon 1978; Senge 1990; Brown 1991; Brown and Duguid 1991; Hock 1995; Leonard-Barton 1995; Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995; Snyder 1996).

The kind of social theory of learning I propose is not a replacement for other theories of learning that address different aspects of the problem. But it does have its own set of assumptions and its own focus. Within this context, it does constitute a coherent level of analysis; it does yield a conceptual framework from which to derive a consistent set of general principles and recommendations for understanding and enabling learning. [p. 3]

Wenger then asserts his view, based on his own set of premises

My assumptions as to what matters about learning and as to the nature of knowledge, knowing, and knowers can be succinctly summarized as follows. I start with four premises:

1) We are social beings. Far from being trivially true, this fact is a central aspect of learning.

2) Knowledge is a matter of competence with respect to enterprises — such as singing in tune, discovering scientific facts, faxing machines, writing poetry, being convivial, growing up as a boy or a girl, and so forth.

3) Knowing is a matter of participating in the pursuit of such enterprises, that is, of active engagement in the world.

4) Meaning — our ability to experience the world and our engagement with it as meaningful — is ultimately what learning is to produce.

As a reflection of these assumptions, the primary focus of this theory is on learning as social participation. Participation here refers not just to local events of engagement in certain activities with certain people, but to a more encompassing process of being active participants in the practices of social communities and constructing identities in relation to these communities.

Participating in a playground clique or in a work team, for instance, is both a kind of action and a form of belonging. Such participation shapes not only what we do, but also who we are and how we interpret what we do. [p. 4]

Wenger starts with an initial (simplified) inventory of components of a social theory of learning, which he eventually details further.

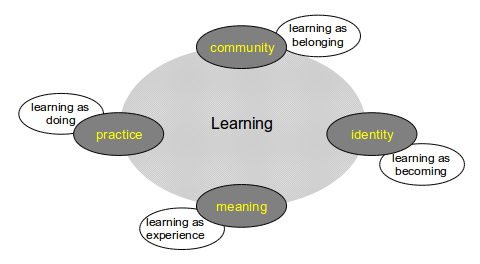

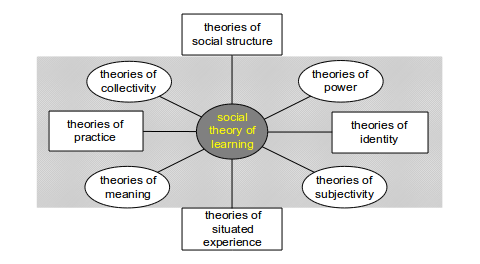

A social theory of learning must therefore integrate the components necessary to characterize social participation as a process of learning and of knowing. These components, shown in Figure 0.1, include the following. [pp. 4-5]

1) Meaning: a way of talking about our (changing) ability — individually and collectively — to experience our life and the world as meaningful.

2) Practice: a way of talking about the shared historical and social resources, frameworks, and perspectives that can sustain mutual engagement in action.

3) Community: a way of talking about the social configurations in which our enterprises are defined as worth pursuing and our participation is recognizable as competence.

4) ldentity: a way of talking about how learning changes who we are and creates personal histories of becoming in the context of our communities.

Clearly, these elements are deeply interconnected and mutually defining. In fact, looking at Figure 0.1, you could switch any of the four peripheral components with learning, place it in the center as the primary focus, and the figure would still make sense. [p. 5]

Therefore, when l use the concept of “community of practice” in the title of this book, I really use it as a point of entry into a broader conceptual framework of which it is a constitutive element. The analytical power of the concept lies precisely in that it integrates the components of Figure 0.1 while referring to a familiar experience. [pp. 5-6]

The prior joint research with Jean Lave on apprenticeship is described as foundations for this perspective on communities of practice.

Intellectual content

In an earlier book, anthropologist Jean Lave and I tried to distill — from a number of ethnographic studies of apprenticeship — what such studies might contribute to a general theory of learning. Our purpose was to articulate what it was about apprenticeship that seemed so compelling as a learning process. Toward this end, we used the concept of legitimate peripheral participation to characterize learning. We wanted to broaden the traditional connotations of the concept of apprenticeship — from a master/student or mentor/mentee relationship to one of changing participation and identity transformation in a community of practice. The concepts of identity and community of practice were thus important to our argument, but they were not given the spotlight and were left largely unanalyzed. In this book I have given these concepts center stage, explored them in detail, and used them as the main entry points into a social theory of learning. [pp. 11-12]

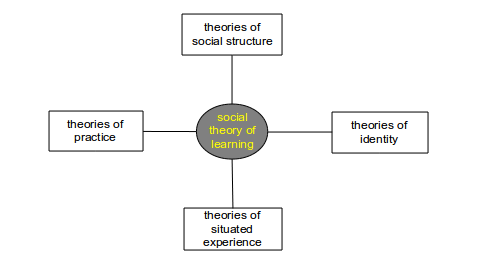

Such a theory of learning is relevant to a number of disciplines, including anthropology, sociology, cognitive and social psychology, philosophy, and organizational and educational theory and practice, But the main tradition to which l think this work belongs — in terms of both influences and contributions — is social theory, a somewhat ill-defined field of conceptual inquiry at the intersection of philosophy, the social sciences, and the humanities.3 In this context, I see a social theory of learning as being located at the intersection of intellectual traditions along two main axes, as illustrated in Figure 0.2. (In the notes I list, for each of the categories, some of the theories whose influence is reflected in my own work.) [p. 12]

3. The roots of social theory go all the way back to Plato’s arguments on the nature of a republic. The tradition was continued by European political philosophy. According to sociologist Anthony Giddens, who has done much to establish social theory as a legitimate and coherent intellectual tradition, the roots of the modern version of social theory are to be found in the work of political economist Karl Marx and sociologists Emile Durkheim and Max Weber (Giddens 1971). But social theory is broader than just theoretical sociology. It includes contributions from such other fields as anthropology, geography, history, linguistics, literary criticism, philosophy political economy, and psychology. [p. 280]

Wenger focuses on the detail of the vertical dimension first.

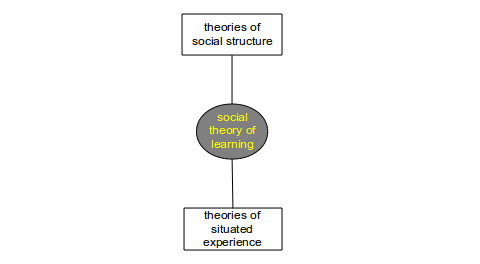

In the tradition of social theory, the vertical axis is a central one. It reflects a tension between theories that give primacy to social structure and those that give primacy to action. A large body of work deals with clashes between these perspectives and attempts to bring them together. [p. 12]

- Theories of social structure give primacy mostly to institutions, norms, and rules. They emphasize cultural systems, discourses, and history. They seek underlying explanatory structures that account for social patterns and tend to view action as a mere realization of these structures in specific circumstances. The most extreme of them deny agency or knowledgeability to individual actors.4 [p. 12]

- Theories of situated experience give primacy to the dynamics of everyday existence, improvisation, coordination, and interactional choreography. They emphasize agency and intentions. They mostly address the interactive relations of people with their environment. They focus on the experience and the local construction of individual or interpersonal events such as activities and conversations. The most extreme of them ignore structure writ large altogether.5

Learning as participation is certainly caught in the middle. lt takes place through our engagement in actions and interactions, but it embeds this engagement in culture and history. Through these local actions and interactions, learning reproduces and transforms the social structure in which it takes place.

4 Giving primacy to structure yields great analytical power because it seeks to account for it wide variety of instances through a unifying underlying structure. This is, of course, the methodological approach of structuralism (Levi-Strauss 1958), but a focus on structure over specific actions and actors is also a characteristic of many approaches that claim no specific allegiance to structuralism (Blau 1975). Even historian Michel Foucault (1966), who distances himself very forcefully from structuralism, ends up giving primacy to historical discourses to the point of questioning the very relevance of individual subjects. Resolving the dichotomy between structure and action is the motivation for Gidden’s “structuration” theory, which is based on the idea that structure is both input to and output of human actions, that actions have both intended and unintended consequences, and that actors know a great deal but not everything about the structural ramifications of their actions (Giddens 1984). Though my purpose is not to address directly the theoretical issue of the structure-action controversy, I will work within assumptions similar to Giddens’s. [pp. 280-281]

5 Concerns with the situatedness of experience are characteristic of a number of disciplines.

- In philosophy, they are rooted in the phenomenological philosophy of Martin Heidegger (1927), whose writings have been brought to broader audiences through the work of philosopher Hubert Dreyfus (1972, 1991), computer scientists Terry Winograd and Fernando Flores (1986). and psychologist Martin Packer (1985).

- In psychology, ecological approaches explore the implications of a close coupling between organism and environment (Maturana and Varela 1980; Winograd and Flores 1986). From this perspective, the environment is viewed as offering specific “affordances” (i.e. possibilities for actions) for specific organisms (Gibson 1979). Situated in this context. cognition is understood as a process of conceptually mediated and coordinated perception (Clancey 1997).

- In education, John Dewey (1922) views thinking as engagement in action, and Donald Schon (1983) views problem solving as a conversation with the situation.

- In sociology, two schools of thought concern themselves with this issue. One is symbolic interactionism (Blumer 1962), and I would include under this category interactional theories of identity (Mead 1934; Goffman 1959). The other school is ethnomethodology (Garfinkel 1967), which has influenced my theorizing mostly through the work of anthropologists Lucy Suchman (1987), on activity as situated improvisation with plans as resources, and Gitti Jordan (1989), on apprenticeship and interactional analysis, and of sociologist Jack Whalen (1992) on the choreography of conversations.

Wenger then shifts the emphasis to the horizontal dimension.

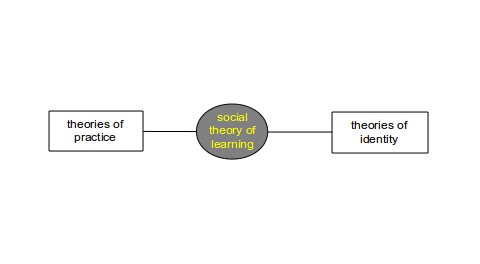

The horizontal axis — with which this book is most directly concerned — is set against the backdrop of the vertical one. lt provides a set of midlevel categories that mediate between the poles of the vertical axis. Practice and identity constitute forms of social and historical continuity and discontinuity that are neither as broad as sociohistorical structure on a grand scale nor as fleeting as the experience, action, and interaction of the moment.

- Theories of social practice address the production and reproduction of specific ways of engaging with the world. They are concerned with everyday activity and real-life settings, but with an emphasis on the social systems of shared resources by which groups organize and coordinate their activities, mutual relationships, and interpretations of the world.6

- Theories of identity are concerned with the social formation of the person, the cultural interpretation of the body, and the creation and use of markers of membership such as rites of passage and social categories. They address issues of gender, class, ethnicity, age, and other forms of categorization, association, and differentiation in an attempt to understand the person as formed through complex relations of mutual constitution between individuals and groups.7

6. Concerns with issues of practice go all the way back to Karl Marx’s use of the notion of “praxis” as the sociohistorical context for a materialist account of consciousness and the making of history (Marx 1944). Since then, concerns with practice have come in a variety of guises as a way to address the constitution of both culture writ large and local activities. My own interest in the concept of practice originated in my work with anthropologist Jean Lave, who had used it as a central argument in her critique of cognitive approaches and her contention that social practice is the key to grasping the actual complexity of human thought as it takes place in real life (Lave 1988; Lave, in preparation). Sociologist/anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu is perhaps the most prominent practice theorist. He uses the concept of practice to counter purely structuralist or functionalist accounts of culture and to emphasize the generative character of structure by which cultural practices embody class relations (Bourdieu 1972, 1979, 1980). Social critic Michel De Certeau (1984) uses the concept of practice to theorize the everyday as resistance to hegemonic structures, and consumption as carving spaces of local production. Literary critic Stanley Fish (1989) uses the concept of practice to account for the authoritative interpretation of texts in the context of what he calls “interpretive communities”. (See also Ortner 1984 for an overview of uses of the concept of practice in anthropology as a way to talk about structure and system without assuming that they have a deterministic effect on action; Chaiklin and Lave 1996 for a collection of perspectives on practice; as well as Turner 1994 for a critique of the use of the concept.) In addition, my understanding of the concept of practice has been influenced by authors who are not avowed practice theorists but whose theories do address related issues. These authors include (in alphabetical order):

- 1) computer scientist Pelle Ehn 1988 — computer-system design as providing tools for professional practices

- 2) activity theorist Yrjo Engestrom (1987) — developmental perspective on historically constituted activities

- 3) social critic Jurgen Habermas (1984) — lifeworld as opposed to system as background for rationality of communication

- 4) urban geographer Jane Jacobs (1992) — different moral systems governing economic and political practices

- 5) sociologist of science Bruno Latour (Latour and Woolgar 1979) — science as practice, factuality as mobilization

- 6) anthropologist Julian Orr (1996) — practice as communal memory through the sharing of stories

- 7) sociologist of science Leigh Star (1989) — boundary issues, translation, marginality

- 8) psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1934, 1978) — engagement in social activity as the foundation for high-level cognitive functions

- 9) social critic Paul Willis (1977, 1981, 1990) — accounts of social reproduction (e.g., social classes) through local cultural production

- 10) philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1953) — meaning as usage in the “language games” of specific “ways of life.” [p. 282]

7. There is a vast literature on identity in the social sciences. While the concept has received much attention in psychology, it has also been explored in social theory as a way of placing the person in a context of mutual constitution between individuals and groups (Strauss 1959; Giddens 1991). Of special relevance to my understanding of issues of identity is the work of other members of the Learning und ldentity Initiative at the Institute for Research on Learning. Linguist Penelope Eckert (1989) explores the practices developed by adolescents with respect to social categories as well as the stylus by which they construct identities in the context of those practices, partictilarly regarding issues of class and gender. Linguist Charlotte Linde (1993) views identity as a narrative, a life story that is cast in terms of cultural systems of coherence and that is constantly and interactively reconstructed in the telling. Anthropologist Lindy Sullivan (1993) analyzes the multiple interpretations that an ethnic community obtains — even internally — thus leading to complex and diverse identities.

Here again, learning is caught in the middle. It is the vehicle for the evolution of practices and the inclusion of newcomers while also (and through the same process) the vehicle for the development and transformation of identities. [p. 13]

The horizontal and vertical axes are supplemented by two diagonal axes, in a refinement.

These two axes set the main backdrop for my theory, but it is worth refining the picture one step further with another set of intermediary axes (see Figure 0.3). Indeed, while the vertical axis is a backdrop for my work, I shall have little to say about structure in the abstract or the minute choreography of interactions. I have therefore added these intermediary diagonal axes to introduce four additional concerns that are traditional in social theory but not quite as extreme as the poles of the vertical axis. For my purpose, they are as far as I go in the direction of social structure or situated experience. Hence, my domain of inquiry is illustrated by the horizontal shaded band. (Note that the resulting figure is not only an expansion of Figure 0.2 but also a refined version of Figure 0.1, outlining in a more detailed and rigorous fashion what I consider to be the components of a social theory of learning.)

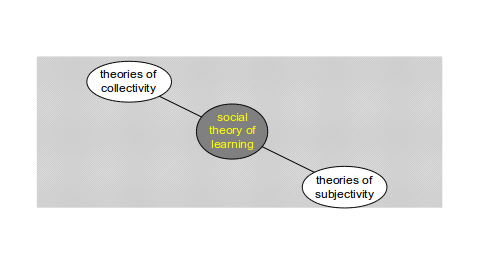

Wenger zooms into the diagonal between theories of collectivity and theories of subjectivity.

One diagonal axis places social collectivities between social structure and practice, and individual subjectivity between identity and situated experience. Connecting the formation of collectivity and the experience of subjectivity on the same axis highlights the inseparable duality of the social and the individual, which is an underlying theme of this book.

- Theories of collectivity address the formation of social configurations of various types, from the local (families, communities, groups, networks) to the global (states, social classes, associations, social movements, organizations). They also seek to describe mechanisms of social cohesion by which these configurations are produced, sustained, and reproduced over time (solidarity, commitments, common interests, affinity).8 [p. 14]

- Theories of subjectivity address the nature of individuality as an experience of agency. Rather than taking for granted a notion of agency associated with the individual subject as a self-standing entity, they seek to explain how the experience of subjectivity arises out of engagement in the social world.9

8. Ever since the early days of social theory, defining basic types of social configuration and analyzing the source of their cohesion and boundaries have been a central concern. Examples include social classes (Marx 1867); societies and communities (Tonnies 1887); groups formed through mechanical solidarity based on similarity, versus organic solidarity based on complementarity; occupational groups (Durkheim 1893); open and closed groups; interest groups (Weber 1922). From a practice-theoretical tradition, the concept of community of practice focuses on what people do together and on thc cultural resources they produce in the process. In different traditions. the following categories are closely related to mine, but with a different focus.

- In social interactionism, the theory of social worlds developed by sociologist Anselm Strauss and his colleagues (Strauss 1978; Star 1989) deals with social configurations created by a shared interest: the world of arts, the world of baseball, the world of business. This theory shares my concerns with perspectives, boundaries, and identity, though my emphasis on practice as a source cohension places learning at the center of the analysis and results in a more fine-grained approach. (Many social worlds are what I would call constellations of practices; see Chapter 5). The tradition of social interactionalism places its emphasis on social groups and on their interactions in forming societies and places of identities. Membership then in social worlds is therefore a matter of affiliation and identity at matter of social categories. By contrast, theories of practice place the emphasis on what people do and how they give meaning to their actions and to the world through everyday engagement. Membership then is a matter of participation and learning, amd identity involves ways of relating to the world. With the notion of practice as a point of departure, it becomes neccssary to pay attention to mechanisms of belonging beyond affiliation, and salient social categories are only part of the story.

- In social psychology, network theory (Wellman and Berkowitz 1998) also addresses a level of informal structure defined in terms of interpersonal relationships. Communities of practice could in fact be viewed as nodes of “strong ties” in interpersonal networks, but again the emphasis is different. What is of`interest for me is not so much the nature of interpersonal relationships through which information flows as the nature of what is shared and learned and becomes a source of cohesion — that is, the structure and content of practice.

- In organizational research, the perspective of occupational communities is contrusted with that of organizational structure as ways of accounting for the formation of identity in practice. While learning is surely a background concern, these studies focus primarily on issues of occupational self-control, deskilling, and career in relation to employment situations (Van Maanen and Barley 1984). [p. 283]

9. The relation of the subject to the object of its consciousness is an age-old question, which has traditionally been framed as a dyadic relation, but which social theory has endeavored to situate in a social context. The notion of the individual subject has even been called into question by poststructuralist and feminist attempts to “decenter” the subject — that is, to move away from a self-standing subject as the source of agency and meaning. Poststructralists decenter the person by giving primary to historically constituted forms of discourse or semiotic structures, of which the “prescence” of the individual is an epiphenomenon. Subjectivity is merely finding a “position” in such a discourse (Foucault 1966, 1971; Derrida 1972; but see Giddens 1979 and Lave et al. 1992 for some constructive critiques). Feminists decenter the person by proposing more encompassing notions of subjectivity (Gilligan 1982) and by reframing classical dichotomies such as public vs. private life and production vs. reproduction (Fraser 1984) or visible vs. invisible work (Daniels 1987; Star 1990b). Two interesting attempts to bring many of these views together are Henriques et al. (1984) and Benhabib (1992).

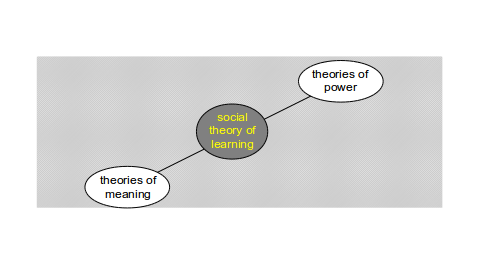

The dimension for focus then shifts to the other diagonal between theories of power and theories of meaning.

The other diagonal axis places power between social structure and identity, and meaning between practice and experience. As the axis suggests, connecting issues of power with issues of production of meaning is another underlying theme of this book.

- Theories of power. The question of power is a central one in social theory. The challenge is to find conceptualizations of power that avoid simply conflictual perspectives (power as domination, oppression, or violence) as well as simply consensual models (power as contractual alignment or as collective agreement conferring authority to, for instance, elected officials).10

- Theories of meaning attempt to account for the ways people produce meanings of their own. (These are different from theories of meaning in the philosophy of language or in logic, where issues of correspondence between statements and reality are the main concern.) Because this notion of meaning production has to do with our ability to “own” meanings, it involves issues of social participation and relations of power in fundamental ways. Indeed, many theories in this category have been concerned with issues of resistance to institutional or colonial power through local cultural production.11

10. Any attempt to deal with the social world must confront issues of power (Giddens 1984). My attempt to develop a concept of power centered on the notion of identity (Chapter 9) does not directly address the concerns of traditional theories of institutionalized power in economic and political terms — for example, private ownership and class relations (Marx 1867), institutional rationalization (Weber 1922; I.ukacs 1922; Latour 1986), state apparatus with legitimation of authority and use of force (Parsons 1962; Althusser 1984; Giddens 1995). My own conception is more in line with theories that consider power relations in the symbolic realm: ideology and hegemony (Gramsci 1957); symbolic or cultural capital (Bourdieu 1972, 1979); pervasive forms of discipline sustained by discourses that define knowledge and truth (Foucault 1971, 1980). Of course, the different forms of power in a society interact, sometimes reinforcing each other and sometimes creating spaces of resistance.

11. The social constitution of meaning has been addressed from a variety of perspectives (I.evi-Strauss 1958; Berger and Luckman 1966; Bourdieu 1972; Lave 1988. Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 1992; Gee 1992; Weick 1995). There is also a substantial literature of resistance in anthropology that studies the strategies people use to produce their own meanings under conditions of oppression, especially under colonialism (Comaroff 1985; Ong 1987). A parallel line of work addresses similar issues under various institutional arrangements in capitalist societies — on the street (Whyte 1943; Hehdige 1979; De Certeau 1984), at work (Hochschild 1983; Van Maanen 1991; Orr 1996), and in schools (Willis 1977; Eckert 1989); Mendoza-Denton 1997).

Having now covered the entire diagram, Wenger opts not for synthesis, but an alternative view on social learning.

The purpose of this book is not to propose a grandiose synthesis of these intellectual traditions or a resolution of the debates they reflect; my goal is much more modest. Nonetheless, that each of these traditions has something crucial to contribute to what I call a social theory of learning is in itself interesting. It shows that developing such a theory comes close to developing a learning-based theory of the social order. ln other words, learning is so fundamental to the social order we live by that theorizing about one is tantamount to theorizing about the other. [p. 15]

The above writing and footnotes represent only an introduction to Wenger’s social theory of learning. There are 200-some pages that build on this brief summary.

The social theory of learning includes not only members of communities of practice, but also the technical world of tools with which work is carried out. Towards the end of the book, Wenger describes four dimension of design for learning, as dualities:

- 1. participation and reification;

- 2. the designed and the emergent;

- 3. the local and the global; and

- 4. identification and negotiability.

These dualities have a tension in their interactions that needed to be addressed. Of the four, I’ve found the second — the designed and the emergent — to be the most interesting.

The designed and the emergent

Practice and identity have their own logic — the logic of engagement, of mutual accountability, of trajectories and boundaries — of which design is only one structuring element. I have argued that the structure of practice is emergent, both highly perturbable and highly resilient, always reconstituting itself in the face of new events. Similarly, the structure of identity emerges out of the process of building a trajectory. It is this emergent character that gives practice and identity their ability to renegotiate meaning anew. In a world that is not predictable, improvisation and innovation are more than desirable, they are essential. [pp. 232-233]

The relation of design to practice is therefore always indirect. It takes place through the ongoing definition of an enterprise by the community pursuing it. In other words, practice cannot be the result of design, but instead constitutes a response to design.

- A piece of software, for example, is the result of design. If it does not execute as expected then there is a bug. The bug indicates a faulty design stemming from an incomplete or inaccurate specification, or from a lack of detailed analysis.

- By contract, practice is (amongst other things) a response to design. Unexpected adaptations of the design are inherent in the process. They do not necessarily indicate a lack of specification. In fact, they may very well indicate a healthy response, which allows a design to be realized meaningfully in specific — but always underspecified — situations.

In this context, increasingly detailed presciptions of practice carry increasing risks of being turned around, especially when a form of institutional accountability is tied to them. Indeed, the response of satisfying (or giving the appearance of satisfying) the prescription may be at odds in fundamental ways with its design intents, as when students focus on test taking instead of the subject matter, or when managers push their quota instead of taking care of business. This suggests the following principle.

- There is an inherent uncertainty between design and its realization in practice, since practice is not the result of design but rather a response to it.

As a consquence, the challenge of design is not a matter of getting rid of the emergent, but rather of including it and making it an opportunity. It is to balance the benefits and costs of prescription and understand the trade-offs involved in specifying in advance. When it comes to design for learning, more is not necessarily better. In this regard, a robust design always has an opportunistic side: it is always — in a sense to be defined carefully for each case — a minimalist design. [p. 233]

Design, from a normative perspective, is about creating or realizing something in the future that does not exist at the current time. Even if we had a full appreciation of the current wants and needs of one or more members of a community of practice, we would never be able to foresee all of the ways that the individual(s) or group would put the design into practice. With a resulting technical design, there will always be a human response to design.

References

Ackoff, Russell L. 1981. Creating the Corporate Future: Plan or Be Planned For. New York: John Wiley and Sons. http://books.google.com/books?id=8EEO2L4cApsC.

Ackoff, Russell L., and Fred E. Emery. 1972. On Purposeful Systems. Aldine-Atherton. http://books.google.com/books?id=R-RSHfnS7VcC

Argyris, Chris, Robert Putnam, and Diana McLain Smith. 1985. Action Science. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. http://books.google.com/books?id=Kt19AAAAIAAJ

Bateson, Gregory. 1972. “The Logical Categories of Learning and Communication.” In Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 279–308. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.http://books.google.ca/books?id=Wfe2t_qzaHEC&pg=PA279.

Brand, Stewart. 1994. How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built. New York: Viking. http://books.google.com/books?id=68DYAAAAMAAJ

Schatzki, Theodore R., Karin Knorr-Cetina, and Eike von Savigny. 2001. The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory. Routledge. http://books.google.ca/books?id=YmPTzh0kiRgC

Wenger, Etienne. 1999. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://books.google.ca/books?id=heBZpgYUKdAC