On my quest for management research based on systems theory, I’ve generally been disappointed since the systems foundations are rarely apparent from a superficial reading. Typically, when I read management research, I get a queasy feeling inside, because a lot of the content written is anti-systemic.

In contrast, when I read Johan Wallin‘s 2006 book, Business Orchestration: Strategic Leadership in the Era of Digital Convergence, I felt strangely comfortable. I attribute this to the lineage from which Wallin has come, so that there is “systems thinking inside”. Wallin completed his dissertation in 2000 in association with Rafael Ramirez. Ramirez is a graduate of the Social Systems Science (S3) program1 at the University of Pennsylvania, and now a professor at Oxford. In addition, Wallin worked closely with Richard Normann, immersing him in the Value Constellation model. I suspect that the average reader would be oblivious to the fine distinctions that systems theory makes. For management researchers, however, such foundations enable a strong scientific foundation, rather than simplified metaphors that break down under scrutiny.

This book is not targeted at academics, and includes many examples (e.g. Nokia, IBM, Toyota) that make the content easily digestable. For my research interests, however, I’m intrigued that Wallin has provided very specific definitions … with which I’m comfortable. I’m not necessarily a believer in objective definitions for business jargon, but they’re sometimes necessary to move forward. Thus, I’ll highlight some common business terms that everyone uses … and few define well.

As a foundation, Wallin starts outside the field of management. Values take us out beyond the traditional domain of business, into the more general field of sociology.

Values are generalized, relatively enduring and consistent priorities of how an actor wants to live. [p. 10]

This definition refers to a 1992 paper by Hans L. Zetterberg presented at the American Sociological Association, but there’s a web-friendly reprint of Zetterberg’s “The study of values” as a 1997 publication. Zetterberg associates with the economic sociology community (e.g. Richard Swedberg), that reflects being-in-the-world in addition to introspection.

Back into the domain of business, Wallin’s value constellation heritage dissolves the academic distinctions between products and services.

An offering is a limited set of focused human activity intended to generate positive customer value and exchange value for the provider of the offering. [p. 10]

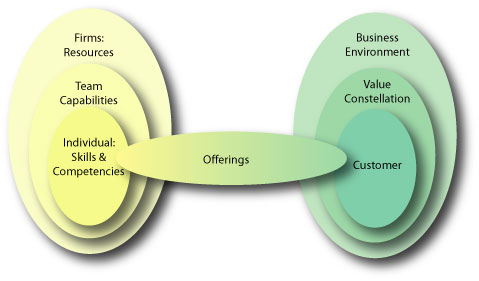

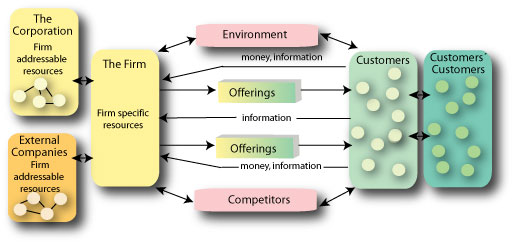

This definition refers back to Wallin’s dissertation in 2000. There’s a subtle inclusion of both customer value (mostly related to use value) and exchange value. There’s a helpful illustration on offerings that doesn’t appear in the book, but is on the Synocus web site.

Businesses create value. In The Democratic Corporation, Russell Ackoff — a prominent systems thinker in management — points out that companies both create wealth and redistribute wealth (in contrast to governments that only have the function of redistributing wealth). Wallin defines:

Value creation is the process of co-producing offerings (i.e. products and services) in a mutually beneficial seller/buyer relationship. This relationship may include other contractors such as subcontractors and the buyer’s customers. In this relationship, the parties behave in a symbiotic manner leading to activities that generate positive values for them.

The actors brought together to interact in this process of co-producing value form a value constellation. [pp. 15-16, editorial paragraphing added]

Coproduction is a systems concept that I’ve read in foundational works both by West Churchman, and his student Russell Ackoff. This definition provided by Wallin has a economic sociology sense that works in business, and doesn’t trample the spirit of system theory. There’s a diagram in the article that has been generalized on the Synocus web site.

(There’s a slightly different definition for “value-creating system” on the Synocus web site, if those specific words are desired for citation).

One of the most popular terms in management is business model. Wallin builds his definition on value-creation.

The business model defines the value-creation priorities of an actor in respect to the utilization of both internal and external resources. It defines how the actor relates with stakeholders, such as actual and potential customers, employees, unions, suppliers, competitors, and other internal groups. It takes account of situations where the actor’s activities may

(a) affect the business environment and its own business in ways that create conflicting interests, or impose risks on the actor; or

(b) develop new, previously unpredicted ways of creating value.

The business model is in itself subject to continual review as a response to actual and possible changes in perceived business conditions. [p. 12, editorial paragraphing added]

This definition references the 2000 book, Prime Movers: Define Your Business or Have Someone Define it Against You, that has Rafael Ramirez as the primary author and Johan Wallin as the second author. There’s a small difference between the definitions in the two books. The 2006 book refers to “an actor”, whereas the 2000 definition refers to “a firm”2. This debate between the individual and the organization is one that is deep in the management research founded on systems theory. (David Hawk and I debate this one all of the time!)

Despite these quibbles, it’s easy to make the linkage from this thinking to the seminar systems theory article in 1965, Emery & Trist’s “The Causal Texture of Organizational Environments”.

With the synopsis above, I haven’t gotten out of the first chapter of Wallin’s 2006 book! The advance that was made between the 2006 work and the 2000 work is the inclusion of “Digital Convergence”. I happened to meet Johan Wallin when we were both participants in the U.C. Berkeley Innovation in Services Conference this past April, and found that his ideas on business orchestration are highly compatible with those of John Hagel and John Seely Brown on productive friction and creation nets. The advantage of meeting in person was that I was able to ascertain that this is a case of “great minds think alike”, rather than a lack of knowledge or conflict between the way these authors think.

Johan and I plan to get together the next time I’m in Finland, when we’ll piece together more fragments from our social networks.

1 I note that the Ph.D. in Social Systems Science was offered at the University of Pennsylvania only between 1975 and 1988. If you wanted to get this degree today, Penn wouldn’t give you one!

2The business model of a firm defines value-creation priorities in respect to the utilization of both internal and external resources. It defines how the firm relates with stakeholders, such as actual and potential customers, employees, unions, suppliers, competitors, and other interest groups. It takes account of situations where its activities may (a) affect the business environment and its own business in ways that could create conflicting interests or impose risks on the firm, or (b) develop new, previously unpredicted ways of creating value. The business model is in itself subject to continual review subject to actual and possible changes in perceived business conditions. [Ramirez & Wallin 2000, p. 77]

References

Johan Wallin, Business Orchestration: Strategic Leadership in the Era of Digital Convergence, John Wiley & Sons 2006 (Chichester, England)

Rafael Ramirez & Johan Wallin, Prime Movers: Define Your Business or Have Someone Define it Against You, John Wiley & Sons 2000 (Chichester, England)