In his writing, Jim Spohrer has referred to The Sciences of the Artificial, written by Herbert Simon in 1996 as foundational to a science of services systems. Due to other priorities, I’ve been try to dodge following through into Simon’s book. Such work isn’t without controversies, such as described by Jude Chua Soo Meng in “Donald Schön, Herbert Simon and The Sciences of the Artificial” published in Design Studies in January 2009. Chua writes:

Donald Schön[‘s] book The Reflective Practitioner (1983) criticized the very technical view of design influenced by logical positivism, and urged design studies to attend to reflection-in-practice. In great part, Schön’s influential criticism was directed at the 1969, 1st edition of Herbert Simon’s The Sciences of the Artificial.

Chua describes revisions in the 1996 third revision of The Sciences of the Artificial that resolves the issues. This is deeper than I’d like to go.

I have to admit that I didn’t fully understand the use of the word “artificial”. Colloquially, “artificial” can be understood to mean something not genuine or made in imitation. Alternatively, it can be opposed to natural, as something man-made or made with human skill. This second meaning became clearer to me as I was reading Sarasvathy et al. “Designing Organizations that Design Environments”, from Organization Studies 2008:

A science of the artificial (or an artifactual science) studies some subset of human artifacts. [p. 331]

The expression of “artifactual” over “artificial” is significant for me, because it bridges sociological research (i.e. organizations) with man-made things (i.e. technology). This has led me do light reading on some articles in three areas:

- (1) Simon (1996) via Jim Spohrer and Sarasvathy et al.;

- (2) Klaus Krippendorkff’s Trajectory of Artificiality; and

- (3) Jelinek, Romme and Boland’s extension of Krippendorff.

The audiences for these writings are slightly different, so cross-disciplinary interpretations and applications lead different places.

(1) Simon (1996) via Jim Spohrer and Sarasvathy et al.

In his blog post on “Service Science 101”, Jim Spohrer writes:

From a research perspective, service science can be conceived of as a science of the artificial. Simon (1996) in “The Sciences of the Artificial” provides a great deal of the conceptual foundations for what we now called service science. The outline of Simon’s book provides an overview of the relevant topics:

- 1. Understanding the Natural and Artificial World,

- 2. Economic Rationality: Adaptive Artifice,

- 3. The Psychology of Thinking: Embedding Artifice in Nature,

- 4. Remembering and Learning: Memory as an Environment for Thought,

- 5. The Science of Design: Creating the Artificial,

- 6. Social Planning: Designing the Evolving Artifact,

- 6. Alternative Views of Complexity,

- 7. The Architecture of Complexity: Hierarchic Systems).

I presume that the structure of the chapters between the 1991 and 1996 edition of this book haven’t changed. Simon’s cognitive orientation towards bounded rationality and artificial intelligence doesn’t align with my worldview. I’ve become too aligned with Hubert Dreyfus’ (negative) views on Good Old Fashion Artificial Intelligence (GOFAI). It’s probably more productive just to focus on the ideas in chapter 5 and 6, rather than be distracted by the others.

In two-thirds of a page, Sarasvathy et. al (2008) concisely summarize the high points of Simon (1996).

Simon included in the sciences of the artificial the study of those “objects and phenomena in which human purpose as well as natural law are embodied”. (Simon 1996: 6). He defined the boundaries for sciences of the artificial as follows (Simon 1996):

- Artificial things are synthesized (though not always or usually with full forethought) by humans.

- Artificial things may imitate appearances in natural things while lacking, in one or many respects, the reality of the latter.

- Artificial things can be characterized in terms of functions, goals, adaptation.

- Artificial things are often discussed, particularly when they are being designed, in terms of imperatives as well as descriptives.

In short, artifacts are fabrications, they exhibit behavior, and they are often described, rightly or wrongly, in intentional terms. [p. 333]

Saying that artifacts “exhibit behavior” and are described with “intentional terms” is becoming more interesting with advances in technology. “Dumb” or passive artifacts are becoming superseded by instrumented, interconnected and intelligence devices in a smarter planet.

On point #3 above, it should be stressed that functions and goals are features of the interaction between the human being and the artifact, and not inherent in the artifact itself. To be rigourous about this systems distinction, in The Democratic Corporation (1994), Russell Ackoff wrote:

… when an essential part of a system is separated from the system of which it is a part, that part loses its ability to carry out its defining function. For example, when the motor of an automobile is removed from that automobile, it cannot move anything, not even itself. A steering wheel removed from a car steers nothing. A hand removed from a body cannot write. A marketing department that has no manufacturing unit or units supplying it with products to sell cannot carry out its function. On the other hand, a manufacturing department whose products are not marketed by a marketing unit cannot continue to produce products for long. [p. 23]

The fourth point on the list leads Sarasvathy et al. to the design perspective on a system of interest by Simon (1996):

[Simon] also defined an artifact as a boundary (interface) between an inner environment and an outer one:

An artifact can be thought of as a meeting point — an “interface” in today’s terms, between an “inner” environment and an “outer” environment, the surroundings in which it operates. Notice that this way of viewing artifacts applies equally well to many things that are not man-made — to all things in fact that can be regarded as adapted to some situation; and in particular it applies to the living systems that have evolved through the forces of organic evolution (Simon 1996: 9).

There are two key elements in Simon’s conception of an artifactual science.

- The first is that the interest is in human artifacts. It is for this reason that a field such as myrmecology (the study of ants) is not an artifactual science, even though ants build artifacts, namely, ant heaps.

- The second element has to do with the relationship between artifacts and natural laws. Simon repeatedly emphasized that natural laws constrain, but do not dictate, the fabrication of artifacts. That is, it is possible to design artifacts. [p. 333, editorial paragraphing added]

Coupling this understanding of artifactual science with Jim Spohrer’s spirit on a science of service systems, I have a greater appreciation for the challenge. We have a history of natural science that goes back beyond the Enlightenment. Our history of a science of service systems as an artifactual science is considerably shorter.

(2) Klaus Krippendorkff’s Trajectory of Artificiality

In sequence, I actually read Jelinek, Romme and Boland (2008) first, but it’s instructive to first review the reference back to Klaus Krippendorf, in The Semantic Turn: A New Foundation for Design (2006). There’s an interesting figure, there.

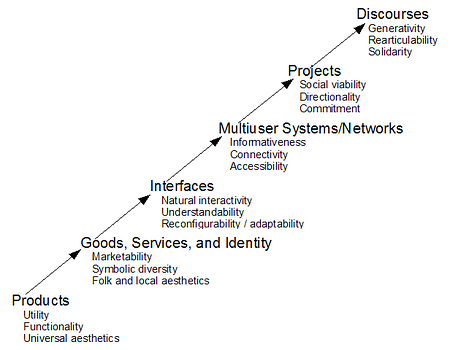

lt is fair to say that the today’s world is more complex, more immaterial, and more public … and designers are facing unprecedented challenges. Figure 1.1 shows a trajectory of such design problems. It starts with the design of material products and continues a progression of five major kinds of artifacts, each adding to what designers can do. This trajectory is not intended to describe irreversible steps but phases of extending design considerations to essentially new kinds of artifacts, each building upon and rearticulating the preceding kinds and adding new design criteria, thus generating a history in progress:

Figure 1.1 Trajectory of artificiality. [p. 6]

The writing is Krippendorf’s book is targeted towards designers. I found similar content expressed more concisely in a 1997 departmental paper on “A Trajectory of Artificiality and New Principles of Design for the Information Age” on the Scholarly Commons at the University of Pennsylvania.

… this trajectory begins with the design of products and passes through five major classes of design problems. Each rearticulates the preceding, thus generating a history in progress: [p. 91]

Products, largely industrial, are designed in view of their utility, functionality, and an aesthetics that, for reasons of applying to large markets, claims universality. In pursuit of these, the responsibility of designers coincides with that of industry which terminates with the end-products of industrial production. Products are conceived for an ideally rational end-user and in disrespect of cultural diversities.

Goods, Services, and (brand, corporate, …) Identities are market and sales driven. Utility and functionality is secondary to recognition, attraction, and consumption. Goods, services and identities are products only in a metaphorical sense for they reside largely in the attitudes, preferences, memories, loyalties, etc. of large populations of people. In developing them, designers are additionally concerned with marketability with symbolic qualities that are widely shared within targeted consumer groups, and their work ultimately drives the generalization of commercial / industrial / corporate culture with its diverse or provincial aesthetics.

Interfaces. Computers, simulators, and control devices are products in the above sense (and where designers concern themselves with their appearances, they also treat them as such). But more important is to see these non-trivial machines as extensions of the human mind, as amplifying human intelligence. Miniaturization, digitalization, and electronics have made the structure of these intelligent machines nearly incomprehensible to ordinary users, and thus shifted designers attention from internal architecture to the interactive languages through which they could be understood and used. Human-machine interactivity, understandability (user-friendliness and self-instruction), (re)configurability (programmability by users), and adaptability (to users’ habits) became new criteria for design. The crown of such one-user-at-a-time interfaces is (the idea of) virtual reality.

Multi-user systems (nets) facilitate the coordination of human practices across space and time, whether these are information systems (e.g. scientific libraries, electronic banks, airplane ticketing), communication networks (e.g. the telephone, internet, WWW, MUDS), or the archaic one-way mass media. Designers of multi-user systems are concerned with their informaticity, connectivity, and the social / mutual accessibility they can provide to users.

Projects can arise around particular technologies, drive them forward, but above all are embodied in human communicative practices. Efforts to put humans on the moon, to develop a program of graduate education in design for the information age, etc. involve the co-ordination of many people. Projects are always narrated and have a “point” that attracts collaborators and motivates them to move it forward. Projects can never be designed single-mindedly. Designers may launch projects, become concerned with their social viability, with their directionality, and how committed its contributors are in pursuit of them, but no single person can control their fate.

Discourses live in communities of people who collaborate in the production of their community and everything that matters to it. By always already being members of communities, designers can not escape being discursively involved with each other and participate in the growth (or demise) of their communities. The design of discourses focuses on their generativity (their capacity to bring forth novel practices), their rearticulability (their facility to provide understanding), and on the solidarity they create within a community. [p. 92]

Reading these six types of artifacts gives me a broader view on the scope that designers take on. Designers will have an impact not only in the physical things on which they’re engaged, but also informational and social aspects — either explicitly or implicitly.

(3) Jelinek, Romme and Boland’s extension of Krippendorff

In the “Introduction to the Special Issue — Organization Studies as a Science for Design: Creating Collaborative Artifacts and Research” (2008), Jelinek, Romme and Boland modify the six types of artifacts presented by Krippendorf into eight:

Extending Krippendorff (2006), we can distinguish, for example, the following kinds of artifacts:

- products (as the end results of a manufacturing process);

- structures (signaling the sequence of authority levels and the distribution of task domains);

- goods, services and identities (as artifacts to be traded and sold);

- management tools and systems, that are created as instruments for accomplishing certain managerial intentions (e.g. MBO, TQM, BPR, 360 degrees feedback);

- human–machine interfaces (e.g. the artifacts that mediate between computers or airplanes and their users);

- multi-user systems and networks, which facilitate the coordination of many human activities across time and space (e.g. guiding people through information systems, check-in lines, or check-out and payment procedures);

- projects and programs (e.g. a new product development project or an employee empowerment program); and, finally,

- discourses, as semantic systems that evolve by being spoken and written (e.g. the narratives around a professional routine, role model, or ideology).

Each artifact in this list has its own jargon and thought world; the criteria for assessment are different for products (e.g. functionality and utility) than for organizational structures (e.g. transparency and accountability). In designing a discourse, criteria may involve generativity and rearticulability (Krippendorff 2006). Taking organizational “discourse” broadly, the design task is to keep the conversation going, involve the interested parties to participate, collaboratively (re)make sense of experiences, in service of goals that also change. [p. 321, editorial paragraphing added]

To help to straighten out the thinking, let’s line up Krippendorf’s 6 types of artifacts against the 8 by Jelinek, Romme and Boland.

| Krippendorff | Jelinek, Romme and Boland |

| products | products |

| … | structures |

| goods, services and identities | goods, services and identities |

| … | management tools and systems |

| interfaces | human-machine interfaces |

| multi-user systems (nets) | multi-user systems and networks |

| projects | projects and programs |

| discourses | discourses |

The perspective on each of these lists is slightly different. Krippendorff is writing primarily for designers, whereas Jelinek, Romme and Boland are writing in a journal for organization scientists. If we refer back to Sarasvathy et al.’s description of Simon’s four boundaries for sciences of the artificial, the two additions — (social) structures, and management tools and systems — would seem to conform. They’re both social constructions, and no less real to the people involved than any of the other artifacts.

Depicting the eight types of artifacts in a stair-step diagram as drawn by Krippendorff might be going too far, though. I can’t definitely say that each of the eight “rearticulates the preceding”, so there’s some space for debate (or convergence) between the authors.

(4) Artifactual science and Services Science, Management, Engineering and Design

Over the year of 2008, there was a subtle shift in suggested description of the field around the science of service systems. It comes out in a footnote to the University of Cambridge IfM and IBM “Succeeding through Service Innovation” report.

… Service Science, Management and Engineering (SSME), or in short Service Science, is emerging as a distinct field to look for a deeper level of knowledge integration2. [p. 5]

2 Considering the integral role of design and the arts in customer experience, SSME could be logically extended to SSMED or SSMEA (Service Science, Management, Engineering and Design/Arts).

Thus, although SSME has become the de facto acronym for the field, SSMED has been suggested as a little more precise. An inclusive description might say that design is included in science, in management, and in engineering. Alternatively, making service artifacts more explicit in science, in management and in engineering can draw on knowledge already developed in design theory.

I prefer “artifactual science” over “sciences of the artificial”. In either case, it’s probable that the layman will remain baffled.