Philosophy underlies the distinction in the three volumes of the Tavistock Anthology: founded on the World Hypotheses of Stephen C. Pepper, the Socio-Psychological Systems Perspective and the Socio-Technical Systems Perspectives are based on Organicism, while the Socio-Ecological Systems Perspective is based on Contextualism.

This thread on contextualism can be traced from the association between E.C. Tolman and Pepper in 1934, through the publication by Emery & Trist in 1965.

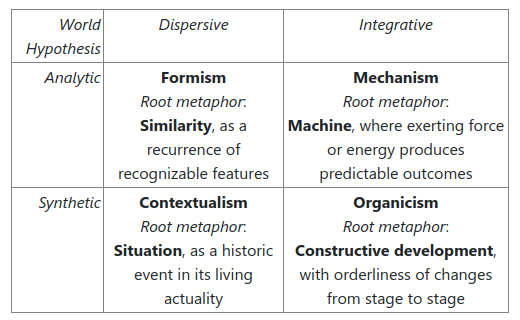

Fred Emery, in the edited paperback on Systems Thinking: Selected Readings (1969), cites World Hypotheses (1942) as a precedent to systems theory. Stephen C. Pepper described the four Relatively Adequate World Hypotheses as two treatments with polarities, that can be structured into a 2-by-2 matrix, shown in Table 1.

| World Hypothesis | Dispersive | Integrative |

| Analytic |

Formism

Root metaphor:

Similarity, as a recurrence of recognizable features

|

Mechanism

Root metaphor:

Machine, where exerting force or energy produces predictable outcomes |

| Synthetic |

Contextualism

Root metaphor:

Situation, as a historic event in its living actuality |

Organicism

Root metaphor:

Constructive development, with orderliness of changes from stage to stage

|

Pepper named four distinct world hypotheses with unfamiliar names, and coupled them loosely with prior philosophical schools. With each world theory, a root metaphor is induced.

- Formism is associated with realism, and the idealism of Plato and Aristotle. Its root metaphor is similarity.

- Mechanism is associated with naturalism or materialism, with philosophers such as Rene Descartes, John Locke, and David Hume. Its root metaphor is a machine.

- Contextualism is associated with pragmatism, and philosophers such as Charles S. Peirce, William James, Henri Bergson and John Dewey. Its root metaphor is a situation (described by Pepper as a historic event, or an act within a setting).

- Organicism is associated with absolute idealism, and philosophers such as George F. H. Hegel and Frances H. Bradley. Its root metaphor is constructive development (described by Pepper as integration, refinement towards an ideal).

Let’s try a concrete example of mammalian births (and human infants, in particular) to get a feel for how the world hypotheses are different.

- With formism, each instance of a birth may be unique, but births have a similarity (e.g. a baby emerges from the mother).

- With mechanism, birth is a process where the mother goes through labour, and (like a machine) pushes out an infant.

- With contextualism, a birth is an situation (or historic event) where an baby can conventionally be traced back with lineage to past ancestors, and forward to future descendants.

- With organicism, a birth is a stage in constructive development of a new being, entering infancy on the way to becoming an adult.

Is there one world hypothesis, on the way to a world theory, that is “right”? From a philosophical standpoint, that depends on the question you’re asking. If we see science as a pursuit of better answers, then we can see philosophy as the pursuit of better questions.

The polarities of the two treatments raise the bar on understanding the metaphilosophy. With authentic systems thinking, “synthesis precedes analysis” [Ackoff 1981, p. 16] is more familiar. The dispersive – integrative polarities are treatments that deserve more attention, when scientific pluralism is ascribed.

The two dimensions from the Table 1 above can be more specifically labelled as “theoretical modes of reasoning” and “theoretical manner for organizing evidence” (following Daley (2000), Table 4). Expanding the cells in Table 1 above:

| World Hypothesis |

Dispersive manner for organizing evidence |

Integrative manner for organizing evidence |

| Analytic mode of reasoning |

Formism

|

Mechanism

|

| Synthetic mode of reasoning |

Contextualism

|

Organicism

|

Along the analytic – synthetic polarities for theoretical modes of reasoning; …

- with an analytic world hypothesis,

- parts in relations are presumed;

- each whole comes inferred;

- e.g. a world theory is reasoned by taking evidence apart; and

- with a synthetic world hypothesis,

- wholes are presumed;

- parts in relations come inferred;

- e.g. a world theory is reasoned by putting evidence together.

Along the dispersive – integrative polarities for theoretical manners for organizing evidence …

- with a dispersive world hypothesis,

- unpredictability (non-determinism) is presumed;

- determinate order is denied;

- e.g. a world theory is organized through evidence that comes as scattered (fused through interpretation); and

- with a integrative world hypothesis,

- determinate order is presumed;

- unpredictability (non-determinism) is denied;

- e.g. a world theory is organized through evidence that fits properly (casting aside “unreal” facts).

Systems thinkers often critical against reductionism, as too analytic, promoting the methodologies with synthesis. Less attention is paid to any implicit premise of (i) unpredictabilty and non-determinism (a dispersive theory), or (ii) determinate order (an integrative theory).

These descriptions raise the bar on understanding basic systems concepts.

- An analytic presumption on part-whole relations doesn’t presume a whole (e.g. a census has an ideal for counting everyone born in a country, yet those who aren’t in the census aren’t excluded as citizens).

- A synthetic presumption on wholes exclusively recognizes parts within (e.g. a teenager who shows up without a birth certificate or any knowledge of birth date won’t be fully identified for most government services, and might be conformed by being assigned an arbitrary birth date).

- A dispersive presumption of unpredictability (non-determinism) takes confluences as novel situations that are unlikely to recur (e.g. pregnant mothers may have an expected due date, but the baby in a natural birth emerges on his or her own schedule).

- A integrative presumption of determinate order takes confluences as predictable, with uncertainties portrayed through probability (e.g. babies normally progress through primary school and secondary school to be considered adults, depending on jurisdiction, somewhere between 16 and 21 years of age).

The World Hypotheses metaphilosophy builds a theory of knowledge based on doubt. For a World Hypothesis to become a World Theory, cognitive refinement improves reliability. Evidence becomes more convincing through increasing scope and precision.

- Improving the scope of a world hypothesis extends the range of circumstances through the collection of more facts.

- Improving the precision of a world hypothesis discriminates more carefully how the collection of facts support each other.

Evidence is rarely observed or experienced directly, so facts as data is less common than danda that is relayed socially.

- Data is “something given, and purely given, entirely free from interpretation”.

- Danda “are not pure observations, but loaded with interpretation” [Pepper 1942, Chapter III, p. 51]

Root metaphor theory builds on maxims, that can be taken as principles or rules on which knowledge is built. Each of the maxims outlined in 1942 are extended with post hoc inferences based on a contemporary appreciation of systems theories.

- Maxim I: A world hypothesis is determined by its root metaphor. In application, several systems theories could be based on a shared root metaphor.

- Maxim II: Each world hypothesis is autonomous. A systems theory should be independently judged on adequacy by the reliability in its corroboration of evidence within. A systems theory should stands on its on evidence, and not on the shortcomings of an alternative theory.

- Maxim III: Eclecticism is confusing. Systems theories are mutually exclusive from each other, based on different root metaphors. Mixing metaphors can introduce conflicting facts, leading to contradiction and a reduction of reliability.

- Maxim, IV: Concepts which have lost contact with their root metaphors are empty abstractions. A systems theory can grow old, so that associated abstractions get taken for granted. Rejuvenation comes through tracing evidence back to the root metaphor.

In essence, each world hypothesis is itself a system of knowledge, with a root metaphor at its core. Improving the reliability of multiple systems theories without contradiction is practical only if they share the same root metaphor.

In the industrial age, organicism can be seen as a primary interest, where an organizational whole is to be formed from parts that are (i) human employees and (ii) machines acquired as capital investments (i.e. socio-technical systems).

In an information age of inter-organizational relations, contextualism can be seen as a primary interest, where incorporated parties (from multinationals to single-person operations) come together in projects that are contracted (and sub-contracted) in non-exclusive agreements for limited durations (i.e. socio-ecological systems).

The question of whether organisicm or contextualism is at play depends on the primary system of interest. The system of interest for one inquiry may be different from the system of interest in another inquiry.

Appendix

As a resource for scholars who would prefer the original words as published, here’s an excerpt from Pepper 1942, Chapter VII describing the content explicated in the tables above.

These four hypotheses arrange themselves in two groups of two each.

- The first two are analytical world theories; the second two, synthetic.

Not that the analytical theories do not recognize and interpret synthesis, and the synthetic theories analysis; but the basic facts or danda of the analytical theories are mainly in the nature of elements or factors, so that synthesis becomes a derivative and not a basic fact, while the basic facts or danda of the synthetic theories are complexes or contexts, so that analysis becomes derivative. There is thus a polarity between these two pairs of hypotheses.

There is also a polarity between the members of each pair, and the polarity is of the same sort in each pair.

- Formism and contextualism are dispersive theories;

- mechanism and organicism, integrative theories.

So, analysis, is treated dispersively by formism and integratively by mechanism, and synthesis is treated dispersively by contextualism and integratively by organicism. [p. 142, editorial paragraphing added]

That is to say, the categories of formism and contextualism are such that, on the whole, facts are taken one by one from whatever source they come and are interpreted as they come and so are left. The universe has for these theories the general effect of multitudes of facts rather loosely scattered about and not necessarily determining one another to any considerable degree. The cosmos for these theories is not in the end highly systematic — the very word “cosmos” is not exactly appropriate. They regard system as something imposed upon parts of the world by other parts, so that there is an inherent cosmic resistance to determinate order in the world as well as a cosmic trend to impose it. Pure cosmic chance, or unpredictability, is thus a concept consistent with these theories even if not resorted to or emphasized by this or that particular writer. [pp. 142-143]

For the categories of mechanism and organicism, however, a concept of cosmic chance is inherently inconsistent and is veiled or explained away on every occasion that it threatens to emerge. If nothing better can be done with it, it is corraled in certain restricted areas of the world where the unpredictable is declared predictable, possibly in accordance with a law of probability. For these two theories the world appears literally as a cosmos where facts occur in a determinate order, and where, if enough were known, they could be predicted, or at least described, as being necessarily just what they are to the minutest detail.

From this parallelism another follows: that the type of inadequacy with which the dispersive theories are chiefly threatened is indeterminateness or lack of precision, whereas the type of inadequacy with which the integrative theories are chiefly threatened is lack of scope. [p. 143]

The intricacies of philosophical language require some extra effort!

References

Ackoff, Russell L. 1981. Creating the Corporate Future: Plan or Be Planned For. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Daley, Michael C. 2000. “An Image of Enduring Plurality in Economic Theory: The Root -Metaphor Theory of Stephen C Pepper.” Doctoral dissertation, Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2118.

Emery, Fred E., and Eric L. Trist. 1965. “The Causal Texture of Organizational Environments.” Human Relations 18 (1): 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872676501800103.

Hayes, Steven C., Linda J. Hayes, and Hayne W. Reese. 1988. “Finding the Philosophical Core: A Review of Stephen C. Pepper’s World Hypotheses: A Study in Evidence.” Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior 50 (1): 97. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1988.50-97, cached at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1338844/

Pepper, Stephen C. 1942. “A General View of the Hypotheses.” In World Hypotheses: A Study in Evidence, 141–50. Berkeley: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520341869 .

Pepper, Stephen C. 1942. “Evidence and Corroboration.” In World Hypotheses: A Study in Evidence, 39–70. Berkeley: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520341869 .